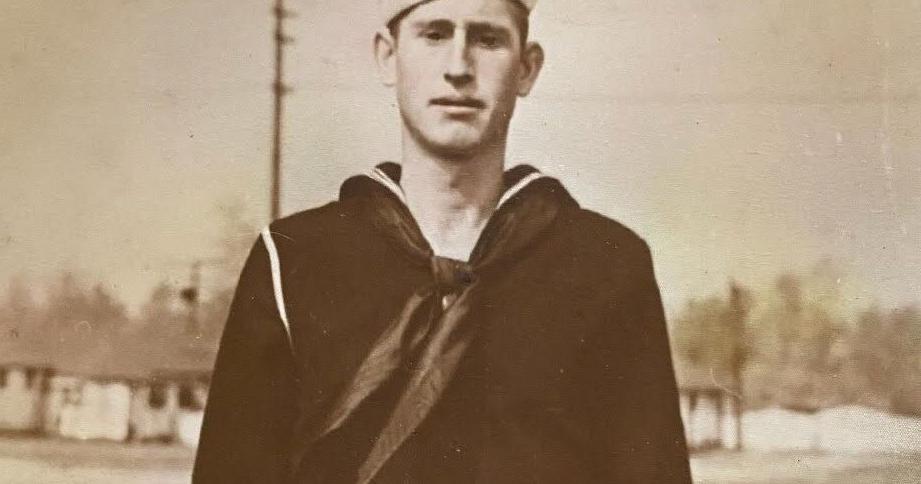

DALLAS CITY, Ill. — Joyce Martin has never met George Price.

But she heard stories from her mother and aunts about her uncle who died in the attack on Pearl Harbor and whose remains have not been identified.

Martin will officiate at a funeral service next month in Dallas City as the Navy Firefighter 1st Class, who was accounted for in August, is laid to rest.

The funeral will be at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, May 4 at Banks and Beals Funeral Home in Dallas. Interment, with full military honors, will follow at Harris Cemetery near the city of Dallas.

Martin’s mother and aunts “always felt like there was never any closure. They always said how hard it was for their mom and dad to lose George,” Martin said.

“It’s just a blessing to feel like I’ve been part of his closure,” she said. “It’s not often that we get to close a chapter on a life that was lost long before we knew them.”

The service will reunite Price’s seven remaining nieces and nephews, including Martin who lives in Burlington, Iowa, and other family members who in some cases have lost touch over the years.

“I know it’s a door that’s been opened by something bigger than us,” Martin said. “Our mothers would be very upset if they knew we hadn’t kept in touch. It’s a second chance for us cousins.

Martin hopes to somehow involve the next generation in the funeral service.

“We want this memory to live on through the generations,” she said. “It’s not something we want to be buried with Uncle George.”

Price, 23, was assigned to the battleship USS Oklahoma on December 7, 1941 when the ship was attacked by Japanese aircraft. The USS Oklahoma suffered multiple torpedoes and quickly capsized, killing 429 crew members, including Price, who was born in Meredosia and raised in Dallas.

“They lived in a little house by the river between Dallas and Pontoosuc,” said Price’s great-niece, Brenda Dusek, who lives near Detroit, Michigan. spent early – and three bedrooms. Six boys in one room, six girls in the other, and two beds in each.

Price was the youngest boy in the family, and Dusek’s grandmother, Nellie Price Ballenger, was the eldest daughter.

“It’s just amazing that this happened and that we can bring him home and place him in his family cemetery” between two of his sisters, Martin said.

Funeral planning began last fall after the family was notified that Price had been considered in August by accounting agency Defense POW/MIA.

Work to account for Price and others lost from the USS Oklahoma dates back to World War II.

From December 1941 to June 1944, naval personnel recovered the remains of the crew, but could not identify many, and then buried them in the Halawa and Nu-uanu cemeteries.

Members of the American Graves Registration Service exhumed the remains in September 1947 and transferred them to the Central Identification Laboratory at Schofield Barracks, where staff confirmed the identification of 35 Oklahoma men.

Unidentified remains were interred in 46 plots at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as Punchbowl, in Honolulu, and in October 1949 a military board classified those who could not be identified, including Price, as non-recoverable.

DPAA personnel exhumed the USS Oklahoma Unknowns from the Punchbowl between June and November 2015 for analysis. Using dental and anthropological analysis, as well as DNA, Price’s remains were identified.

“Just finding some of his remains was a gift from God to us,” said Martin, who has provided DNA two or three times over the years to help with the identification process.

“It’s so special to bring him home,” Dusek said. “We went to the Punchbowl, the cemetery in Hawaii where George’s name is carved in granite with all the people who lost their lives. My husband has said now that they will put a (rosette) next to his name with his remains identified.

Dusek worked with Danyelle Harrison Henning at Harrison Monuments on a headstone for Price.

The federal government is providing an engraved flat marker for veterans, which will be installed as a vertical marker in the cemetery on a granite base with flower vases incorporated into the design.

Henning said the monument served an important role as a reminder.

“One is, of course, to honor and recognize veterans simply because of what they did for our country and how we are able to live our lives today,” he said. she declared. “Another is to provide education to younger generations. If we don’t recognize, show our appreciation and remember what our veterans did, our future generations will take for granted the great country we live in. This didn’t happen by accident. People had to work to bring the United States to where it is today.